My first image of that continent was its circus.

I remember my childhood as continuous drought broken by brief rains. In July, when our circus practiced outdoors, it was hot by nine and unbearable before eleven. Then we would follow the ringleader into the sharp still air of the tent and listen to stories of his life.

Born into hippie royalty in California, Michael drifted south, seeking an older model of the folk theater. He found it in the street clowns of Mexico City and their performances of sickness and poverty, summoning these qualities in public so that they might hold less terror in private. He was captivated by the darkness and charisma of their gestures, which seemed to inherit the grandeur of that older continent where their tradition had emerged. He studied his trade at one of the last great institutions of its kind. On his return, he shared it with us.

The tent's striped canvas smelled as if it were slowly melting. We listened attentively, but we had a fixation with pulling up clumps of grass and smearing them across one another's bare legs. Michael told us his grandfather’s stories, which always built to unintended cannibalism on tropical islands, mixed in with his own memories of the clowns and with bootlegged tapes of Cirque du Soleil that we watched on a tiny TV. Too young to draw rigorous distinctions, I received all of this information with the same sense of immediate relevance. I was left with basic uncertainties as to whether we were being shown a work of theater or a newsreel straight from the heart of a darker land. I imagined Mexico City to be in Europe, and all of that region to be devoted to productions of this same fantastic and cruel circus.

Michael had assembled a group of locals who seemed in their own way expats of the Old World. Dance was taught by Lark, an elongated woman whose avian features and languid movements formed my earliest impressions of sexuality. Twirling through clouds of white face powder in a room lined with mirrors, we chanted “We can become anything through movement!” until the words loosened and we fell into mimicry of the jungle animals that she called out. For most of the year, Edwin was chief puppeteer of the Solstice—our town’s largest parade where papier-mâché sun gods strode on stilts through our Spanish Colonial downtown—but during the summer, his wire-frame glasses and doe-like features were confined to the shadows of a portable trailer, praising us softly as we coaxed sheets of cardboard and reels of thin-gauge wire into unstable life. I saw in these adults’ gestures and mannerisms that same high tone and darkness, traits that were impossibly foreign to a child of Trader Joes. I emerged from their lessons into blinding mid-afternoon and white stucco suburbia, wrecked among heathen dreams, taunted by phantom accordions and the slow movement of velvet curtains.

A decade later I was in night classes at the National Centre for Circus Arts in London, studying trapeze in the generating chamber of a Victorian power plant. From the platform near the top of the atrium, gripping a bar wrapped in sweat-stained surgical tape, you could look down onto the old brick ledge that once held the room's mezzanine, a hundred years' gone, where bottle caps and wrappers tossed by engineers still lingered among clumps of moss. All of the other students were Russian women. On the platform between swings, they would whisper words that danced darkly for the equipment: trapieza, vozdushnyye polotna. They flew with a cold precision, as if they could turn off parts of their bodies at will, allowing them to dangle so beautifully out under the lamps—the sharp alien bones of their pelvis and rib cage as exaggerated as a carapace by the contortions of flight. When one of their limbs broke from this spell and flailed or when they lost hold of the bar part way through some inversion and flew off into the net, they would let out high shrieks and bare their teeth.

I was driven across the Old World by atmospheric longings, leading me in each city to the same quarters, the back alley performances and concertina shops, the ethnic enclaves of the Circus Europeans. In Porto’s Teatro de Marionetas I found a few recently painted rooms packed with astounding puppets: their scrunched red faces rendered in clay and papier-mâché. I sat in the basement flicking through recordings of past performances, captivated by the cruel pitch of the language and the movement of the puppeteers who slid around the shadows of the stage, somehow more visible than their puppets. Rounding a corner in Copehagen’s Kristiania, I caught a glimpse through a pair of faded blue doors of a family juggling clubs in deep shadow. A Parisian ringleader on the Petite Ceinture pulled his show horse’s face close to threaten it in a tone that proved his unbroken lineage. When a friend told me that Basel’s carnival held the key to it all, I was desperate to believe him. He refused to send me photos, so I waited nearly a year and then arrived early, knowing only that Fasnacht continues uninterrupted for 72 hours, a period the Baslers call in their guttural Low Alemannic dialect die drey scheenschte Dääg: the three most beautiful days.

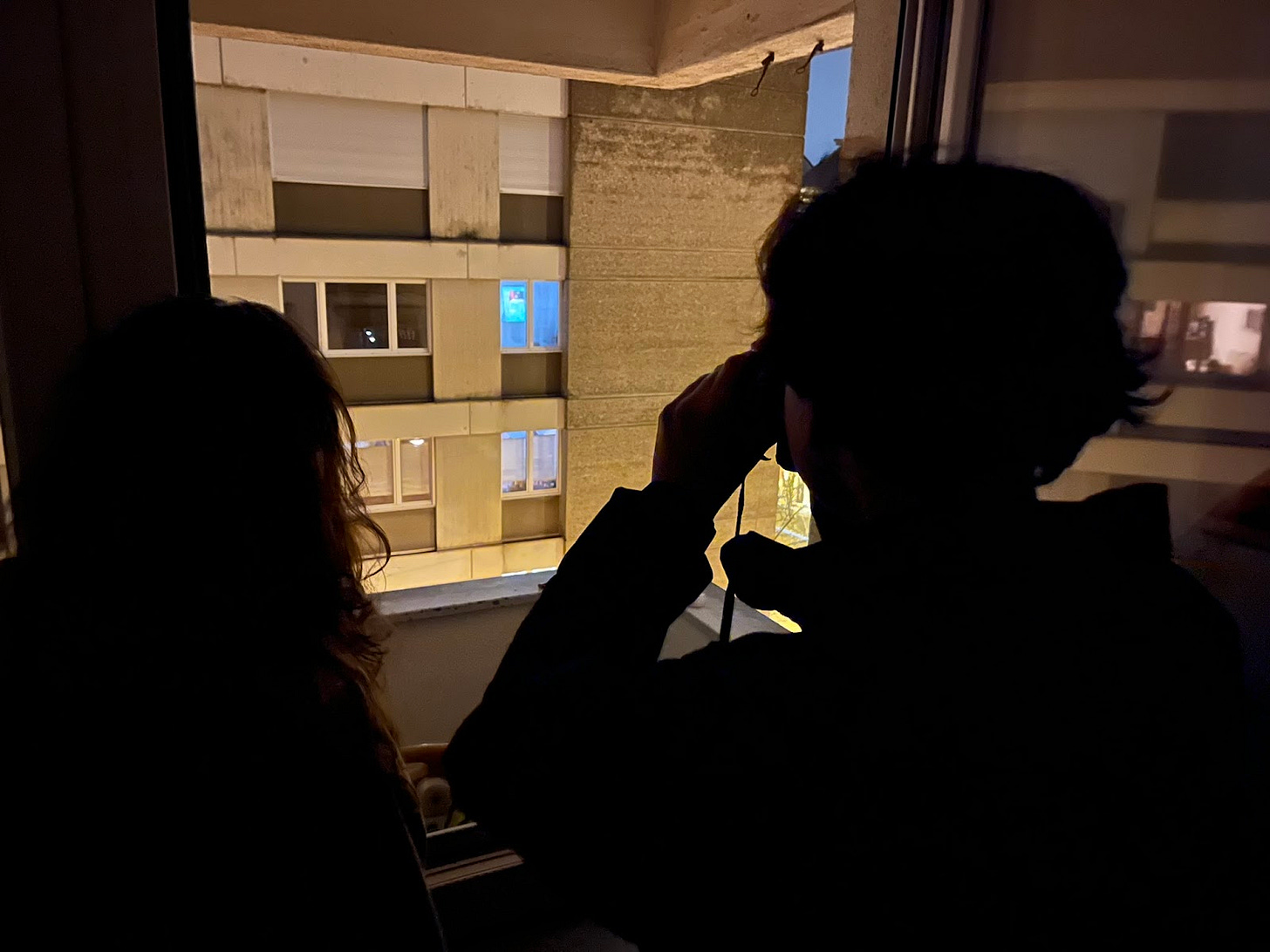

Ortiz lived on the only bad street in Switzerland. His apartment was a narrow white box on the third floor with two little vestibules for the entryway and kitchen. The light offered by the one wall of glass made it feel like we were figures inside a cramped diorama. We would sit for hours on the balcony looking down at the door of a traphouse, a drooping tenement with a heavy metal door that swung through the night. Ortiz called the house’s patrons Svenoids, named for their habit of approaching and shouting up to an open window "Sven—Sven!" until they were let in to complete whatever fetid task awaited them. They were natural clowns, prowling around the road as if engaged in some secret errand and yet immediately identifiable by their stilted gait. They moved like a bad animation, spoke only in stage whispers, high whistles, and barks. Whenever two or more convened, they would fall into long Shakespearean disputes until the scene reached some height of dramatic intensity, and then I would yell out "Kokain!" in the voice of a Turkish market vendor or toss down torn pieces of pretzel, causing them to fall on one another in a rage.

The other residents of Efringerstrasse seemed aware of the activity but completely undisturbed by it. While the Svenoids snarled and scrabbled in the street, or dragged in stolen bikes and threw themselves in desperation against Sven’s locked door, a young Swiss couple would eat pasta silently and then lie awake in bed for hours, staring immobile into one another’s eyes, their drapes wide open. Ortiz’s girlfriend, a cat-eyed Connecticut psychologist, guiltily proffered a pair of binoculars and we all fell into an electrified focus.

It was as if the city had been synthesized from a set of desires that were recognizable and compelling—as close as any had come—but ultimately Ortiz’s rather than my own. He took me on a long walk up the west bank of the Rhine, over a bridge, and back down the east, crossing through three countries accompanied by only the subtlest changes in the particular forms of malaise on display, past long lines of Circus Europeans waiting with bags of discounted clothing to exchange one paper receipt with the border guard for another—not sullen, merely vacant, enthralled by a stillness that only residents of the Old World can achieve. And as we walked, Ortiz whispered that these same silent shamblers were gathering underground as they had for a thousand years, practicing in the kellers with their families’ “cliques” for what would begin that evening.

Midnight came. We gathered with instant coffee in the upstairs office of the Literature department. No light was allowed. I was introduced to a series of rural British accents that I could not see in the darkness of the room. We perched around the window as if preparing to fire at a passing motorcade—and indeed down on the street dozens of shapes were gathering, forming themselves into rough blocks of shadow, the silhouettes of swordsmen and enormous birds. At 4am exactly, the street lamps went out. I could feel Ortiz quivering beside me, on the precipice of some ecstatic release. Then a single voice cried out Morgestraich, vorwärts marsch!—and a thousand lanterns were lit at once, illuminating the battalions of night arrayed below, their high shrill piccolos and Basler snare drums rising to a tune unheard in the developed world: the march of the forgotten toys, sickly and ecstatic.

That music enacted a change, as if heralding our entry into a zone with a new physics, a cessation of normal motive and time. We descended through the old high doors of the university and were swept into the crowd, following the long row of swaying lanterns down a crooked road. There were brief lines of sight that stretched for miles, then all at once they were closed off as a row of houses slid across the road ahead. As we moved in uneasy orbit between the swaying cliques, more detail emerged—how some lanterns were smaller and worn like helmets, how others were large and painted in the jagged tessellations of stained glass, supported on carts that were pulled by three or four men; how the music was not one unified song but the overlay of dozens of subtly competing cliques, each in their own uniforms: the harlequins and napoleonic soldiers, grim pinocchios and birds; and how the cliques’ members seemed at first young in their strong movements, but looking closely at their uncovered hands and necks revealed them to be deeply wrinkled, the sort of hands you would find in nursing homes and funeral parlors.

We flowed with thousands to gather in a stagnant swirl at the confluence of a number of roads. Every direction, close enough to kiss, the vast and unmarked faces of the Swiss revelers were framed in the crowd. They looked through us, benevolent and unseeing. When we eventually broke free and climbed to the low parapet of the Munsterplatz, we were struck by a sudden vision, very far down and reflected in the flowing surface of the Rhine, of two cliques meeting on the Mittlere bridge. It all recalled Huizinga's image of the processions of Late Medieval Paris:

They continued from the end of May into July and involved ever different groups, orders or guilds, ever different routes and ever different relics... All were barefoot with empty stomachs, members of parliament and poor Burghers alike; every one who was able carried a candle or a torch. There were many small children with them. Even the poor folk from the villages around Paris came running on bare feet... And heavy rain fell almost constantly during the entire period.

My memory of the next few days is fragmentary. The three most beautiful days adopt their own surreal pacing, a bookmark out of time. We would return to the apartment to nap as needed, mostly in the late afternoon; otherwise we rode new currents, aware of the hallucinatory transition from the spare and haunting Morgestraich to the brash Guggenmusik, that completely separate hell that emerged on the nights known as Cortege, where parades ran in two frantic concentric rings in opposing directions around the city’s modern center, with farm trucks loaded with nightmarish Alasatian Waggis hurling oranges into the crowd, their children dumping confetti on anyone not wearing a small enameled Blaggede. We would flee this miasma into the depths of a clique’s keller, listen there to snarling orations under grotesque murals, and emerge to find that it was somehow now dawn—and that a single battalion was marching through the low gray light, tireless and shrill as they patrolled some lonely back alley. I passed a sign announcing the Consulate of the Kingdom of Lepmuria but could never find it again. Once, hours or perhaps days later, as I lost my companions and walked alone down a narrow road, I marveled at a clique bearing a lantern down a wavering parallel street, until I realized that the whole scene was only a reflection in a shop window: that the men clad in dark leather were walking beside me.

The people of that city were without a doubt the most beautiful I had ever seen, but it was an entirely inert beauty—a set of traits that elicited no response or sensation. When you turned a corner to find a group of clique members unmasked, they seemed to exist out of time, locked in scenes of slow immaculate leisure: emerging from a feathered breastplate to smoke benignly, as if captivated by the sudden anachronism of their position, the mask of a bird or demon disregarded at their feet. With their floss-thin hair swept behind their ears and their grey-blue eyes, they looked bloodless, literally lacking in blood, sculpted from some drab clay into masks of nobility and unfeeling calm. They smoked like extras on a film set in a silvery photo of early Hollywood. Only two or three times during that whole weekend did I see a clique member smile—and only then with a sort of grim satisfaction in throwing their trash on the ground, a delight allowed in Basel only during Fasnacht.

Houllebecq said that Switzerland is the most depressing country in Europe. Of those countries I've seen, I can only agree, and yet Basel was the first place to uphold my fantasy of the circus, to let it waver out in the world, dark and inhabitable for a full three days. I wondered constantly how a people so inert could come up with costumes of such expressive power, wondered what their relationship with those costumes could possibly be. They seemed the unthinking heirs of much older forms, still potent but no longer understood.

Otherwise across the city there is a bare acknowledgement of the facts of life: the slow passionless sunbathing of the locals on the Rhine, the way signs for public toilets depict the Waggis pissing against a wall. Against this backdrop, Fasnacht is all the more inexplicable. There is an undercurrent of lurid violence and carnality in the lanterns and costumes, not attributable to any one detail, just an awareness that it’s happening down in the deeper kellers, ferocious and yet completely without enjoyment. Even their food implies a brief savage satisfaction, these people who are entirely without desire—pale sausages draped over small paper plates and cubical slices of brown honey cake impaled by vertical forks.

A diffused and aimless libertarianism animates Fasnacht. When I asked locals to translate cliques’ Zeedel, thin flyers of satirical verse as long as a CVS receipt, it was difficult to say exactly what was being mocked or resisted. The costumers took care to distinguish the features and headwear of their racial caricatures, as if aware only of their own atmospheric standards, the necessity only of a ferocious energy. Some of Ortiz’s expat peers left the city each year in protest—less because of any one aspect of the event than because of its tone, an old world frivolity incompatible with contemporary understandings of progress. Then there were moments when a battalion of four dozen Mickey Mouses would pass by with tubas and the whole event would seem less agential than you had first thought—as if this sudden lapse in taste revealed the Baslers as merely provincial and overly incredulous, on the precipice of a globalism that would smooth their horror away.

At dawn on March 12th we looked up and the city was empty, all traces of the carnival wiped clean overnight. Somehow destabilized by this sudden loss, driven to jittery irritability by a phantom Guggenmusik, Ortiz and I were already unable to look one another in the eye. We stole a bag of groceries from Migros, walked to a truck stop at the edge of the city, and there, as a light rain settled over the highway, silenced somehow by the immensity of what we had seen, we took spluttering drags from a wet cigarette under a cardboard sign labeled Krakau and, like exiles of a dark dream, cast weary eyes to the northeast.

Share this post